Once You’ve Eaten Food From a Lovo, Life Will Never Be the Same

May is Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month! According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month began as Asian/Pacific American Heritage Week in 1978 with a joint congressional resolution. Congress expanded the observance to one month in 1992, renaming it Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

In 2022, the Biden administration designated May as “Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Heritage Month,” reportedly to bring broader visibility to Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities.

During this year’s Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, United Way creative services manager Jannette Whippy, a Fijian American, shares her experiences growing up in the Pacific.

I used to tell people who asked that I was half Fijian and half American. Now I know I am not half of anything; I am double, both, more. Fijian and American. Being mixed race is an expansion of identities, not a reduction.

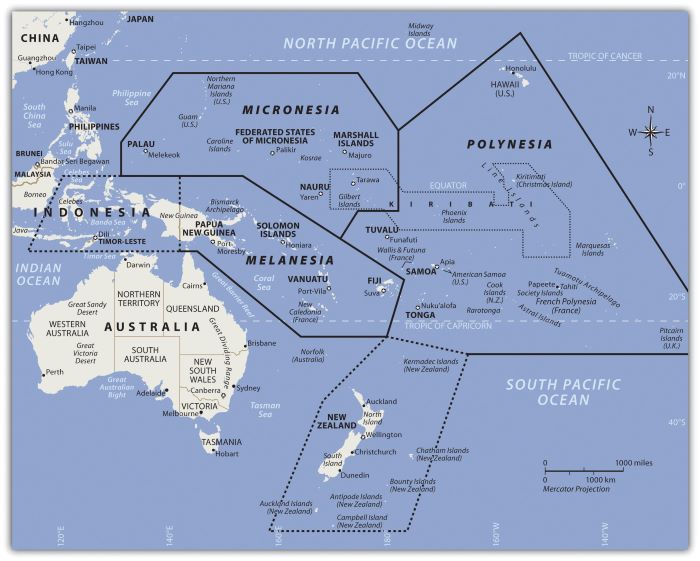

I was fortunate to grow up on three very different Islands in the Melanesian and Micronesian areas of the Pacific: Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Guam. These three places are all included in the “PI” part of “AAPI,”and they are all completely, totally, different.

I spent the first five years of my life in Suva, Fiji. Seeing photos of my childhood there brings back sense memories: sticky, sweet sugarcane sticks, wind rustling in coconut trees, water splashing, salty skin drying in the sunshine. Most of my experiences in Fiji are of visiting family: diving in the colorful reefs of Taveuni, driving the barely maintained roads of Savusavu to explore our family land, sitting on pandanus mats drinking Kava with cousins, and eating smoky, savory food served out of earth ovens called lovos.

My formative years were spent in Lae, Papua New Guinea (PNG). We lived on a university campus; our yard had a guava tree, a lemon tree, a mango tree and a pineapple patch.

Looking back, the variety of food available on trees was astounding. My friends and I prowled the empty, paved roads on our BMX bikes and ran through back yards playing expansive games of tag. My international school was for foreigners: It was year-round, had uniforms and was a boarding school. When I wasn’t in a classroom, I was running around barefoot with my friends. Life was messy hair, bike maintenance, tree climbing and fruit eating. I was 12 when we left Papua New Guinea for Guam.

How to lovo, featuring Dr. Tarisi Sorovi-Vunidilo

Guam was my first time, technically, living in the United States. This tiny island territory was so very different from the green, verdant jungles of PNG. It was so small, and all the trees were short (typhoons are common). The houses were boxy and entirely made of concrete. The US military influence was overwhelming, with a massive air base in the north and an equally massive naval base further south.

On Guam, I discovered the joy of diving, and worked as a diver for a tourist submarine (we would lure fish to the submarine windows for the people inside). I stayed away from the barracuda food (those fish do not mess around) and stuck with feeding the angel and parrot fish (smaller, less likely to take a finger). All my summer jobs required ocean diving time.

Living in Guam, I learned of the importance of land ownership and stewardship. The land taken for military bases was either paved over and trampled down, ignored or used as waste disposal. The military doesn’t have the same connection to the land that the native inhabitants do, and their care of it reflects that disconnection.

The diversity of people and cultures in the Pacific is extraordinary. I understand the need to band together for political clout. However, just as “Asian” does a disservice to the many different cultures and experiences of people grouped into that term, Pacific Islanders are not a monolith either. Even within the three regions (Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia) there are tremendous differences. Celebrating and learning from the rich culture, heritage and land stewardship practices of these places will only serve to build a stronger future for planet earth.

The map above shows the three areas of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. Below is information about all three areas.

Melanesia*

North of Australia, the region that borders Indonesia to the east is called Melanesia.

The name originally referred to people with darker skin but does not adequately describe the region’s current ethnic diversity.

Micronesia*

North of the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea is the large region of Micronesia.

The “micro” portion of the name refers to the fact that the islands are small in size.

Only one island exceeds one square mile in land area.

Polynesia*

Polynesia is a land of many island groups with large distances between them.

Polynesia has a mixture of island types ranging from the high mountains of Hawaii, which are more than 13,800 feet, to low-lying coral atolls that are only a few feet above sea level.

Independent Countries of Micronesia: Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati (Western), Marshall Islands, Nauru, Palau. Other Island Groups of Micronesia: Guam (US), Gilbert Islands (Kiribati), Northern Mariana Islands (US), Wake Island (US).

Independent Countries of Melanesia: Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu. Other Island Groups: of Melanesia: New Caledonia (France).

Independent Countries of Polynesia: Kiribati (eastern), Samoa, Tonga, Tuvalu. Main Island Possessions of Polynesia: American Samoa (US), Cook Islands (New Zealand), Hawaiian Islands (US), Pitcairn Islands (UK), French Polynesia, which comprises the Austral Islands, the Marquesas, Society Islands and Tahiti, the Tuamotu Islands.

Step up your knowledge of these areas with these YouTube videos from Kava Bowl Media:

Pacific Level Up 5: Melanesia 101 with Dr. Tarisi Sorovi-Vunidilo

Pacific Level Up 4: Meet Micronesia

Pacific Level Up 6: Polynesia 101

* Referenced from the World Regional Geography: People, Places and Globalization by Royal Berglee, Ph.D., Chapter 13.1, University of Minnesota, 2012. The text was slightly modified for space and has been used in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Comments