Black History Month: Preserving Seattle’s African American Hub

Throughout February, United Way of King County has joined others in commemorating Black History Month, an annual observance in the United States that recognizes the achievements and struggles of African Americans.

United Way commemorates the observance this year by spotlighting Seattle’s Central District, an area that once housed the city’s largest concentration of African Americans and served as a hub for the local Black experience.

According to the Washington state history site HistoryLink.org, Seattle’s Central District is an urban swath of land bounded by East Madison Street on the north, Jackson Street on the south, 12th Avenue on the west and Martin Luther King Jr. Way on the east.

But back in the day—i.e., about 15-20 years ago and generations earlier—you didn’t need an official demarcation or sign posting or a Rand McNally atlas to know you were there. The sights, sounds and smells of the area bellowed boldly: It’s where the Black folks in Seattle live.

“I used to get my hair done at the corner of 23rd and Union, and that was for me the moment when I said, ‘I’ve arrived in the Central District, I’ve arrived in the Black community,’” said Andrea Caupain, president and CEO of Byrd Barr Place, a social services organization that has been in the Central District for more than 50 years. You couldn’t go a block or two without seeing someone you knew. It was a feeling. We drove into the Central District from Kent every weekend to be with Black people.”

United Way president and CEO Gordon McHenry, Jr. grew up nearby in North Beacon Hill, a racially mixed area, but he and his family worshipped at Mount Zion Baptist Church in the Central District, whose pastor went to college with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The church was the cradle of the area’s civil rights movement.

“Where I grew up in North Beacon Hill was very diverse, but it was guaranteed that when I was in the Central Area, which we knew later as the Central District, that’ was predominantly Black,” said McHenry. “It was a different sense of energy and belonging; this was a special place and it was our place.”

Seattle’s Central District was New York’s Harlem, Chicago’s South Side, Tulsa’s Black Wall Street and Miami’s Overtown. Originally the unceded traditional land of Indigenous people, the Central District is one of Seattle’s oldest surviving neighborhoods, and it has been home to Jewish, Japanese and Dutch residents as well.

But it became synonymous with African Americans ever since Black entrepreneur William Grose arrived in Seattle around 1861. He went on to become a successful businessman and purchased 12 acres of land between what is now East Olive Street and East Madison Street at 24th Avenue, according to HistoryLink.

Grose built his residence there, and other Blacks flocked to the area—some to be around folks from their background and others because racially restrictive covenants kept people of color from moving elsewhere in the city. The Central District became known to many as the Colored District or by its initials, the C.D., and was a haven for all of Black society: low income, working class, middle class and wealthy. According to the city documents the area was as much as 90 percent Black in the 1960s.

Before there was COMMUNION, the Central District restaurant named one of Condé Nast’s best in the world, there was Ms. Helen’s Soul Bistro, a Central District staple known for its gumbo and oxtails. Folks bought goods at the Promenade 23 Shopping Center. Garfield High School boasted (and still boasts) the best basketball teams in the city.

Then, there was the music. The Central District produced Quincy Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Ernestine Anderson and Sir Mix-A-Lot. Even Ray Charles spent a couple of years there; he made his name on the Seattle jazz circuit and ultimately established his own sound after mimicking artists like Nat King Cole.

But much of the Central District’s glory days are uttered in the past tense. Like many other former Black communities across the nation, its residents of color have been displaced due in large part to gentrification. According to local news reports, the Central District is now about nine percent Black, the culmination of an African American decline that has spanned decades.

The irony is that generations ago the Central Area was deemed an undesirable place to white homeowners and realtors.

The federal government stepped in and offered programs designed to help families build wealth through homeownership. Yet government officials termed some areas—namely where Blacks and other people of color lived—as too risky for the program. On housing maps, those areas were shaded in red—a process that became known as redlining—and loans were denied to Black applicants in those areas, even though they had good credit.

Eventually, areas like the Central District became marginalized from many of the nation’s post-Depression-era economic turnarounds. For years, African Americans managed to uphold the area’s charm and vibrance, despite weathering discrimination in local hiring and de facto housing practices. Soon, many who could leave the Central District opted for more affordable towns in South King County—including Kent, Renton, Auburn and Federal Way.

Many who remain struggle to keep pace with the area’s high property values and costs. They are an example of the area’s stark income inequality, its burgeoning tech boom that helped generate more than 68,000 millionaires in King County (according to TNS Financial Services) but left many in the area behind.

“Seattle has enjoyed a very robust tech and innovation-driven economic growth, and our community has not participated equitably in that, and a lot of displacement pressures and gentrification have been directly connected to that,” said Wyking Garrett, president and CEO of Africatown Community Land Trust, which acquires and develops land assets necessary for Black communities to grow in the Central District and other parts of the state.

Caupain said that once the Central District’s demographic changed, so did its importance in the eyes of the city.

“For years, we asked for traffic calming techniques on 18th Avenue, where cars were speeding up and down,” Caupain said. “We called the city and the department of transportation to see what they could do to alleviate it, and it fell on deaf ears.

“We noticed a significant difference ten years ago, when there were white people moving in and more higher income people moving in,” Caupain added. “The city put a curb out there, a stop sign and [other traffic reduction measures]. Talk about overkill. We knew that white people had moved in, and their voices where often heard, when we saw that street change.”

That has left King County’s Black community at a crossroad: preserve and rebuild a once-vibrant Black haven or grow stronger roots where they are now planted. United Way has helped the communities with both: The Black Community Building Collective is a coalition of 15 Black-led organizations brought together by United Way to build relationships and form strategies that impact the Black community in both Seattle and beyond.

The Collective includes the African American Leadership Forum in Kent, Reclaiming Our Greatness in Renton and the two aforementioned Central District groups, Byrd Barr Place and Africatown Community Land Trust. Byrd Barr Place continues to provide basic needs and policy advocacy for former residents who have been displaced—some of whom still come for services despite now living in North Pierce County.

Africatown’s acquisitions include acquisition of the site of the former Liberty Bank Building (the area’s first Black bank), which now has 115 units of affordable housing that are marketed to the Black community. The bottom floor is reserved for retail space and is home to COMMUNION restaurant. They and other groups are working to ensure the Central District will always be home to Seattle’s Black experience.

We’ve been here, we’re still here and we should be here in the future.

Wyking Garrett, Africatown Community Land Trust president and CEO

“At the point where the Black community has been completely written off in the Central District, and I would say Seattle as a whole, Africatown was a vanguard voice in saying, ‘No. We’ve been here, we’re still here and we should be here in the future,’” said Garrett.

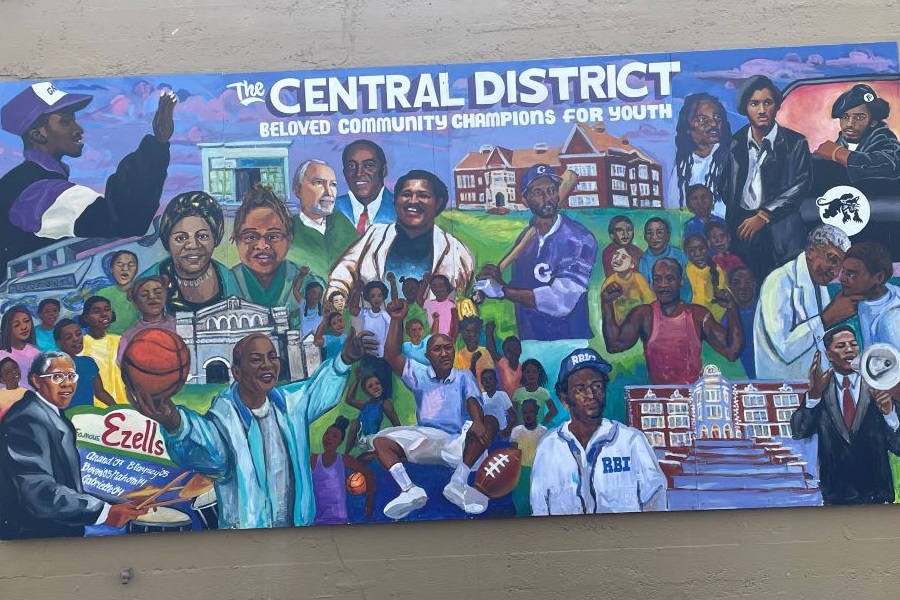

“And we need to chart a course,” Garrett added, “where the legacy of those who contributed to making not [just] the Central District a community but contributed to Seattle as a city, all the way back to William Grose, should not be lost and just become a part of history books and museums and murals. There should be a living, thriving, vibrant Black community as a part of Seattle going forward.”

Comments